Fellow Travelers: The Canterbury Tales and IIIF

by Benjamin Albritton

Those who study medieval texts are often faced with the fact that multiple versions of those texts exist in manuscripts scattered across collections, libraries, institutions, and sometimes continents. The rapid growth of availability of digital images of those manuscripts affords scholars and students the opportunity to compare witnesses more easily than in decades past, when we relied on scratchy microfilm copies or expensive in-person visits to the physical manuscripts. As valuable as online images are, we are still struggling with usability: both what we want to do, and how we want to do it.

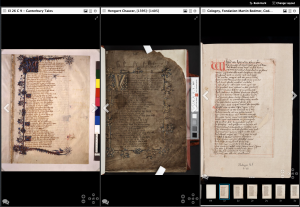

Interoperability, that unwieldy buzzword that has nearly as many definitions as practitioners, provides one path on the road toward a true digital medieval studies. In this context, the term means: the ability of software tools to use content from anywhere on the web through common APIs. Rather than diving into the details of such a vague statement here, let’s pose a question: “What if I wanted to compare the opening pages of the Canterbury Tales from two different manuscripts?”

The Hengwrt and Ellesmere Chaucer mss.

The answers to that question are varied. A researcher could:

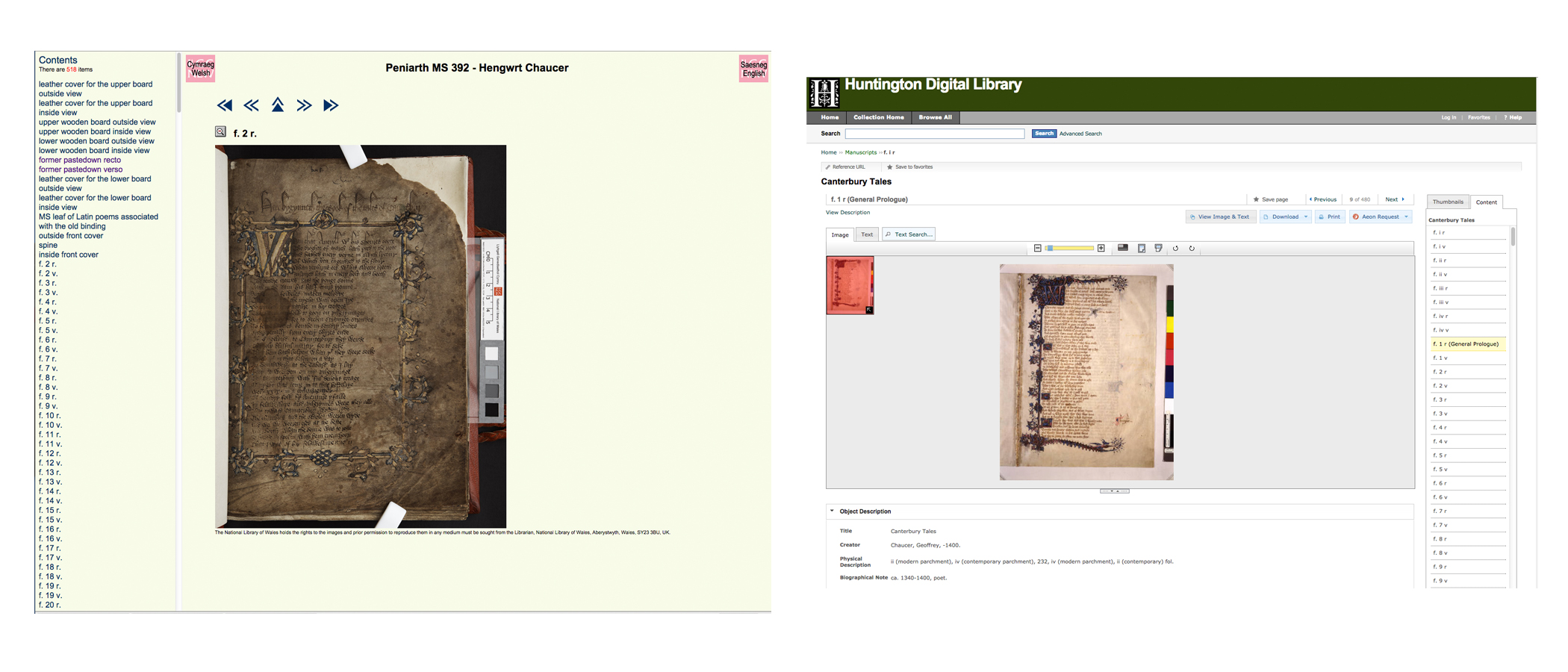

- Open up two different web sites in a browser (see screen caps above of those of the Huntington Library and the National Library of Wales)

- Compare published facsimiles – putting printed images side-by-side

- Acquire copies of images from the books and compare them on one's own computer

- But what if there was another (possibly better) way?

See this demo in its native environment here.

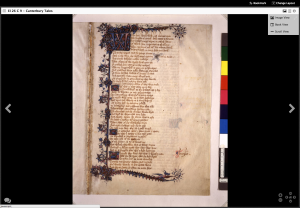

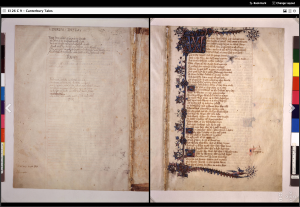

This demo opens with the General Prologue of the Canterbury Tales from two of the most famous Chaucer manuscripts: the Ellesmere Chaucer held at the Huntington Library (MS El 26 C 9) and the Hengwrt Chaucer held at the National Library of Wales (Peniarth MS 392). These images aren't being rehosted here at Stanford, they are coming directly from their home institutions (so the hosts can track usage of these images). The embedded version of this demo is somewhat limited, so follow the link to the full example here.

What are we looking at?

Each institution has published some data (a 'manifest') that lets us know where to find the image files for each object, as well as additional information like the sequence of the images, some description, page labels - just enough information to drive a piece of viewing software like the one in the demo above. They have also made their images available via the IIIF image API - a set of rules that allows many different types of software to access images held at different institutions the same way. So, we are seeing images coming from Los Angeles and Aberystwyth in a viewer hosted at Stanford. Because of this arrangement, it may take some time for one of the manuscripts to load.

In a world where content is everywhere online, being able to access that material in predictable ways and re-use it has become extremely important. The list of libraries, museums, and other institutions supporting the IIIF image API is growing rapidly - which means that we, as users of those images, are benefitting from a surge of development to produce tools that take advantage of a wide swath of content.

More about Mirador

Mirador is one such tool (there are others, see the IIIF website for more), and its specialty is comparison: across folios, across objects, across collections, across repositories... It allows multiple viewing modes, as many viewing windows as your screen real-estate will allow, and has emerging annotation components for reading and creating annotations (the latter functionality is not turned on in this demo).

Mirador allows us, in a simple demo like this, the ability to:

- zoom in to any detail using the plus/minus buttons (or mouse scroll)

- work through the text page by page, comparing details like decoration, paleography, textual variants, etc. (use the arrow keys to move sequentially through the books)

- examine one book in detail (or two, as the embedded viewer above demonstrates)

- examine one book as a series of openings, something many manuscript scholars prefer to the "disembodied page" image approach

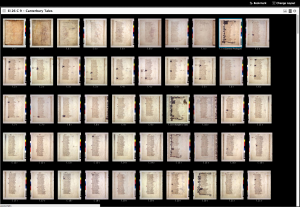

- switch to a thumbnail view to navigate within the book

- add in a third manuscript for comparison (or four, or five...)

Mirador, like the other IIIF-compliant viewers that are being developed, provides a number of different options for working with content online. This short video provides a little bit more information about navigating through the tool and its options:

How To Make Your Own Comparison Demo

One of the nicest things about the IIIF approach to shared content is that it lowers the barriers to building light-weight demonstrations like this for teaching and research purposes. The institutions that host the images are on the hook for long-term access and preservation, so it's not necessary to host your own copies of the images. Further, the viewing software that is available is primarily free and open-source. So how do you make your own Chaucer (or anything else) comparison demo? A few simple steps get you up and running:

- Install Mirador (or a comparable IIIF-compliant viewer) either on your own machine or deployed on the web (code available at github). There are instructions for installation in the README and on the project wiki .

- Find the IIIF manifests for the content you want to add to your instance. In this case, the two Chaucer manuscript manifests can be found at:

- The Ellesmere Chaucer at The Huntington Library

- The Hengwrt Chaucer at the National Library of Wales

- Bonus , Cologny, Cod. Bodmer 48, via e-codices

- Add these manifests to your Mirador instance by:

- adding them through the "Add new object from URL" box, which temporarily adds the manuscripts to your workspace, or

- configure your index.html file to include those manifests all the time

That's pretty much it. The trick, as you might imagine, is finding out where the manifests are for the manuscripts you're interested in. The community is starting to come to grips with this issue, but at the moment it's not terribly easy. Good IIIF partners like e-codices or the new Digital Bodleian site from Oxford University provide the manifest URL as part of the metadata for each of their objects (Oxford even gives us a IIIF logo as a guide to the manifest, which is very helpful as a visual signal to users).

Looking Forward

One could imagine building course- or publication-specific instances of a demonstration like this - something that would provide a starting premise and context (two Chaucer manuscripts showing the same text, for instance), but allow students, readers, or casual viewers the ability to explore such a juxtaposition in new, interesting, and hopefully unexpected ways. There are thousands of manuscripts available now from interoperable repositories that can be used, and - with more institutions joining IIIF each year - thousands more in the offing. As the tools get easier to use and configure, it will be fascinating to see what becomes possible for medieval studies.

We're already seeing a number of scholars and projects taking advantage of the opportunities offered by IIIF (Jeffrey Witt, at Loyola University and the Biblissima project to name two, alongside platforms like Broken Books at Saint Louis University). What could you do in your own practice with resources and tools like these?

Other online resources:

- Short description of the Hengwrt Chaucer from The National Library of Wales

- Short description of the Ellesmere Chaucer from The Huntington Library

- The Hengwrt Chaucer Digital Edition by Estelle Stubbs

- CTP2: Canterbury Tales, transcriptions and collations by Peter Robinson and Barbara Bordalejo

- Digitally Enabled Scholarship with Medieval Manuscripts at Yale, with a project led by Alastair Minnis which provides an analysis of inks and pigments used in hand produced copies of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and other contemporaneous Middle English works.

Many thanks to Glen Robson and Dafydd Tudur at the National Library of Wales, and to Vanessa Wilkie and Mario Einaudi at the Huntington Library for their help in making these materials available.